by Stephen M. Scalzo

Headline image: Quincy Railway 110 was the pride of the fleet and the most modern single-truck streetcar in America when this photo was taken about 1912. All photos from the Stephen M. Scalzo Collection except where noted.

Quincy started talking about the formation of a street railway system before the close of the Civil War, but it was not until the fall of 1864 that a company was formed by a group of its citizens. On February 11, 1865, the Quincy Horse Railway & Carrying Company secured a charter from the state legislature for the exclusive privilege of operating a street railway for a period of 50 years. The bill that had been passed by the legislature permitted the sale of 1,000 shares of $100 per share stock to finance construction. The franchise for the company was prepared by two recognized Quincy attorneys, Nehemiah Bushnell and Orville H. Browning, with the former soon acquiring the company's stock and becoming the first president. E.H. Buckley was hired to manage the company.

In 1867, construction of the first 1.3 miles of trackage running west on Maine Street from Sixth to Fifth Streets, and on Fifth north to the city limits at Locust Street, began. When five cent horsecar service began operating in the fall of 1867, the company had only three 12-foot four-wheel cars. Four horses, two of which were used at one time, kept two cars moving. Later, mules from Missouri were purchased to replace the horses, because of the steep grades on the system, and they supplied power for the horsecars for the next 20 years. Turntables were placed at Fifth and Maine Streets and at Fifth and Locust Streets for turning the cars. Rails consisted of two-by-four timbers set up on edge with a strip of iron on top for the horsecars to roll over. The first office and barn was located on the northeast corner of Fifth and Locust Streets. The company earned nothing during its first two years of operation.

In 1869, Lorenzo Bull became president and E.K. Stone became superintendent. On June 10, 1871, the city council passed an ordinance taking over the powers granted to the company by the state charter and granted a new franchise. The company was then given permission to build trackage on Fifth, Eighth, and other north-south streets between Fifth and Eighth, for the purpose of extending service to Woodward Cemetery. Various plans for new branches were delayed by the city's overall financial problems. In July 1871, the property owners along Maine Street east of Sixth Street subscribed $10,000 for extension of horsecar service. By 1872, the Maine Street line had been extended from Sixth Street east to the Fairgrounds, and another line was operating north on Twentieth Street from Maine Street to Highland Park. Also, about that time, the company built a new $11,000 carbarn and stable at Twentieth and Maine Streets. By 1879, the company had 15 cars and 60 mules.

Car 36 was likely part of Quincy's original order for electric cars in 1891.

On November 18, 1889, the city council revised the franchise, giving the company the right to electrify service. The Broadway and Tenth Street extensions were opened just before construction began on electrification in 1890 by the Thomson-Houston Company. Late in the afternoon of January 1, 1891, the first electric streetcar began operating in Quincy over the five foot gauge trackage. The powerhouse on First and State Streets supplied electric power for the overhead to power the 13 new St. Louis-built streetcars over 11 miles of trackage. In April 1896, a $12,000 fire destroyed the north carbarn. By 1897, the company had 13 miles of track over which it operated 31 streetcars and seven trailers.

Open car 78 is on Hampshire Street passing the square on the State Street line, probably around the turn of the century. Quincy had more open cars for a system its size than perhaps any other street railway in Illinois.

On August 5, 1898, the McKinley Syndicate purchased the system for $360,000, and immediately spent $100,000 to increase trackage, with extensions on South Fourth, Broadway, and North Fifth to the Soldiers Home. A new carbarn capable of storing 28 streetcars was constructed at Twentieth and Hampshire Streets. Earnings were $100,450 in 1900. The population of Quincy was 36,252. By 1901, the company had 17 miles of track with 35 streetcars and seven trailers. In March 1901, the South Fourth Street line was completed and placed into service.

A 70-series open car is seen at the attractive waiting shelter built at the Soldiers Home. This building still stands, and not only that, the recently built Amtrak station on the outskirts of town was designed to imitate its style as well.

We are looking north on 5th from Maine around the turn of the century as car 38 approaches. The large four-story building block directly over the streetcar is still there.

On March 6, 1910, the Quincy Railway was incorporated to acquire the company. In May 1912, construction began on a four-mile crosstown line on Twelfth Street and east to Walton Heights, and a short extension of the State Street line to the Country Club. During October 1913, a branch west on Adams and south on Fifth to Indian Mound Park was completed and placed into service. In 1914, the company earned $213,876. In 1915, Snyder's Rapid Transit Service opened a rival jitney line, and it operated until May 11, 1916, when the Illinois Utilities Commission halted its service. By 1913, the company had almost 23 miles of trackage operating 16 closed and 22 open streetcars, 12 closed and 14 open trailers, one motor and two trailer work cars, and one snow sweeper. During 1916, the company instituted one-man streetcar service, the first in the state.

Quincy operated some pretty homely-looking single-truck cars. Here, car 90 is shown signed for "Q.Depot."

We are looking east on Maine from 5th Street, with open car 69 visible in the distance. The distinctive building on the left still stands.

In April 1919, new machinery was installed in the powerhouse to permit use of electricity from the Keokuk Dam on the Mississippi River and to permit the old steam plant to be kept for emergency standby service. Later that month, work began on a complete rehabilitation of the trackage in preparation for the 25 new four-wheel one-man Birney streetcars that were placed into service during the fall of 1919 and the spring of 1920. Fares were increased from five to seven cents (or four tickets for 25 cents) on July 1, 1918, and that action resulted in a court battle with the city, which the company won in July 1919 when the Illinois Public Utility Commission authorized the fare increase.

Lightweight car 110 and the other three cars of its class were revolutionary lightweights when they were built in 1912. They were precursors of hundreds of Birneys built for systems across the country over the next 15 years. Here, car 110 is posed in front of the Quincy Railway carbarn.

Open car 69 has trailer 91 and a more diminutive single-truck open trailer in tow, with another three-car train led by open car 67 following, on the Walton Heights line. The photo likely dates to sometime not long after the line opened in 1912.

During the period of 1920 through 1924, the system lost 978,000 riders because of the increased ownership of automobiles. In May 1923, the company was acquired by the Illinois Power & Light Company. As paving costs grew on streets with trackage, a decision was made to convert the more lightly traveled lines to buses.

A 20-series open car (center) and another open car meet at 5th and Hampshire on the square sometime around 1914.

One of Quincy's open cars is shown on 20th Street just north of Maine outside the carbarn. The building behind it served as an office and waiting room.

On September 2, 1925, the first eight new buses arrived for use on the South Eighth and State Street lines; authority was given to abandon those two streetcar lines on October 13, 1925. On October 12, fares were increased to 10 cents. Rail removal began on South Eighth Street on March 12, 1926, and was completed on March 26. On February 1, 1926, the city council passed an ordinance permitting the removal of trackage on the Broadway line, with the Illinois Commerce Commission authorizing abandonment on March 24. On August 25, 1927, the Walton Heights line was cut back to Twentieth Street, and three Birney streetcars were converted to double-end so that they could be used on that stub end line. On September 20, 1927, the Walton Heights line was further cut back to Elm and Eighteenth Street, and on August 22, 1928, the remainder of the line was abandoned. During 1927, five surplus Birney streetcars were sent to Cairo.

Photos of the Quincy Railway's Birneys are surprisingly rare. Here, car 205 is shown signed for the CB&Q depot. The single-ended car lacks a front pole and has front and rear doors on this side.

This postcard view looking east from Maine (misspelled) and 5th shows one of the company's Birneys. Krambles-Peterson Archive.

When it became apparent that the streetcar system was operating at a loss, a decision was made to convert the remaining streetcar lines to buses. On March 3, 1928, the company was authorized to abandon the Soldiers Home line, and on March 28, 1928, authority was received to abandon the North Fifth Street line. On April 1, 1928, buses replaced streetcars on those two lines. In July 1929, the Maine Street line was cut back to Twenty-fourth Street. By 1930, only 4.9 miles of trackage remained in service over five routes.

We are looking northeast at Hampshire and 8th as a Birney approaches in the foreground. At center-right is the Quincy Post Office, which still stands, while at left the Vermont Street Methodist Church, torn down c1952, dominates the skyline.

Finally, late on the evening of February 28, 1931, Birney streetcar 214 left Washington Park for its final run to close out regular streetcar service. On March 2, the company ran three Birney streetcars over the remaining trackage, with city officials and newspaper reporters joining the general public in the farewell trip. Following abandonment, the remaining trackage was dismantled and the streetcars scrapped.

This article was edited and laid out by Frank Hicks. Thanks to Ray and Julie Piesciuk and to Richard Schauer for making available the materials from the Stephen Scalzo Collection that made this history possible.

Quincy Railway Roster

All cars 5' gauge - this is not a comprehensive all-time roster

20 - single-truck closed trailer

21-28 - single-truck double-end 10-bench open cars - Danville 1909 (ord#512) - 19,500 lbs. - Note 1

33, 34, 36, 38 - single-truck closed cars - photo link - Note 2

40-46 - single-truck open trailers

50 - single-truck closed trailer

55 - single-truck closed car - Brill - 2 x WH 49 motors

56-57 - single-truck closed cars - Stephenson 1901 - 2 x WH 49 motors - 21,500 lbs.

58-62 - single-truck closed cars - Pullman 1898 (ord #909) - Peckham truck - 2 x WH 49 motors - 22,000 lbs.

65-75, 77 - single-truck double-end closed cars - Brill 1899 (ord#9034) - Brill 21E truck - 20,000 lbs. - Note 4

76, 78 - single-truck open cars - 19,500 lbs.

81-84 - single-truck closed cars - American 1906 (ord#680) - Brill 21E truck - 2 x WH 49 motors - 21,000 lbs. - Note 5

86 - single-truck closed car - Pullman - 2 x WH 49 motors - 22,000 lbs.

87-90 - single-truck closed cars - American 1906 (ord#680) - Brill 21E truck - 2 x WH 49 motors - 21,000 lbs.

91-97 - single-truck open trailers - Note 6

101-109 - single-truck double-end closed cars - Danville 1910 (ord#554) - Curtis truck - 2 x GE 88 motors - K-10 control - 32,000 lbs. - 33'8" long, 8'2" wide

100, 110-113 - single-truck closed cars - St. Louis 1912 (ord#958) - St Louis 78 truck - 2 x WH 328 motors - 23,400 lbs. - photo link - Note 7

200-224 - single-truck single-end Birney cars - American 1919 (ord#1205) - Brill 78M1F truck - 2 x GE 258 motors - K-10 control - 28' long, 7'9" wide - Note 8

400 - single-truck single-end ultra-lightweight closed car - St. Louis 1916 (ord#1081) - St Louis Special truck - Note 9

(no number) - single-truck snow sweeper - McGuire-Cummings - 3 x WH 49 motors - K-10 control - Note 10

(no number) - single-truck sand car - 2 x WH 49 motors

Note 1: One of these cars was rebuilt by QR as a closed car, while two more had sides added from the belt rail down but without windows.

Note 2: No roster information on hand, only photographic evidence; these appear to be the original electric cars ordered in 1890, which if true would mean they were part of a series of 13 cars; some may have been destroyed in the 1896 fire; car 33 at least survived long enough to have its ends enclosed and acquire a Brill 21E truck.

Note 4: Photos show car 77 to have had a Peckham truck (link)

Note 5: Builder uncertain; contemporary rosters suggest that cars 81-84 (1906) and 87-90 (1908) were built by Danville, but American Car company order lists show six cars numbered 87-90 (and?) built for Quincy in 1906; other sources suggest the six American-built cars were instead numbered 81-86

Note 6: Electric Railway Review printed that Quincy ordered eight open cars and two closed cars, all single-truck, from Danville during 1908. It's possible, but conjecture, that these were numbered 91-98 and 99-100 respectively.

Note 7: Dr. Harold Cox's seminal work "The Birney Car" points to this series, designed by J.M. Bosenbury and built for Quincy Railway, as the first true pre-Birney cars built, as they incorporated single-truck design, lightweight construction, prepayment fare collection, single-man operation, and safety car equipment.

Note 8: Cars 204, 208, 221, 223, and 224 transferred in 1927 to Cairo Railway & Light, there renumbered 103, 102, 100, 101, and 104 respectively. Three or four other Birneys, numbers unknown, rebuilt as double-ended cars in 1927.

Note 9: Experimental car designed by J.M. Bosenbury, lettered Illinois Traction System but used in Quincy, resold in 1921 via St. Louis Car Company (ord#1254) to Arkansas Valley Interurban Railway as their car 100.

Note 10: Sources differ as to whether the company had one or two snow sweepers. One snow sweeper was ordered in 1909. One snow sweeper was resold to Peoria as their 1003.

Car 33 appears to be one of the original 1891 cars, heavily rebuilt with partially enclosed platforms and a Brill 21E truck. The car is signed for the Front Street line.

Car 62 is shown in an 1898 Pullman builder's photo painted for the Soldiers Home line, which was constructed at the same time as this car. Krambles-Peterson Archive.

Smart-looking open car 68, also signed for Front Street, is shown in an undated photo sitting in front of the main 20th Street carbarn. This building still stands and is in use as a bus garage. Quincy Railway later built another carbarn, a metal-sheathed structure, in the area visible behind car 68 on the right.

There is uncertainty surrounding the origins of the 80-series cars built in the 1906 period. It's likely that car 88, shown here, and its fellow closed cars were built by American.

Danville-built car 105 is shown in this 1910 builder's photo. The unusual Curtis single truck and two-man, Pay-As-You-Enter fare collection design are apparent.

Car 110, the most photographed car on the system, is shown sometime around its date of construction in 1912 signed for the South 12th Street line.

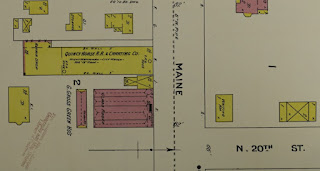

This 1898 Sanborn map shows the old Quincy Horse Railway & Carrying Company barn on the south side of Maine Street just east of 20th. The new carbarn, the one still standing, was built on the east side of 20th north of Maine Street the same year this was printed.

This metal-sheathed carbarn was built sometime after the 1898 main carbarn, which itself is visible on the left side of the photo. We are looking southwest from Hampshire and 20th.

Route Map

Thank you for "publishing" this information on this and other smaller street railways properties. I (and I am sure others) find this interesting and informative.

ReplyDeleteThe other Stafa in Ohio

Bosenbury car 100 ended up on Oskaloosa(IA) Light & Traction, another McKinley property. Not sure if it was delivered from the builder to Quincy or Oskaloosa. St. Louis Car Co shows this unit as an order by itself, separate from the units built for Quincy or Wichita.

ReplyDeleteMark Sims

The choice of a five-foot gauge is interesting; I'm not aware of any other non-standard gauge electric line in Illinois. Typically, this happened because standard gauge was prohibited by the city in its charter, to eliminate any possibility of operating freight trains in the streets -- as ludicrous as that may seem due to the flimsy construction of most street railway trackage.

ReplyDelete